The Predictability Triangle

Introduction

All models are flawed, but some models are useful. That’s what my economics teacher told me when I was learning the Phillips Curve.

Little did I know, the concept applies to other fields too!

A few months ago, we released an article titled ‘The Resolutional Circle’ which attempted to simplify debate mechanics into a visual model.

In that article, we represented all mandates encompassed by the resolution, plans, and counterplans as circles, with the size of the circle representing how unlimited it is and the distance from the resolutional circle representing how predictable it is.

After thinking for a little bit, it should be clear that the latter half of that collapses pretty quickly.

The dilemma stems from the fact that overlapping mandates sometimes have a huge difference in predictability.

Take for instance, T: ‘Should’ doesn’t force immediacy is probably the most predictable interpretation of that word. Its mandates are quite expansive and actually encompass the mandates of T: ‘Should’ does force immediacy, which is comparatively smaller.

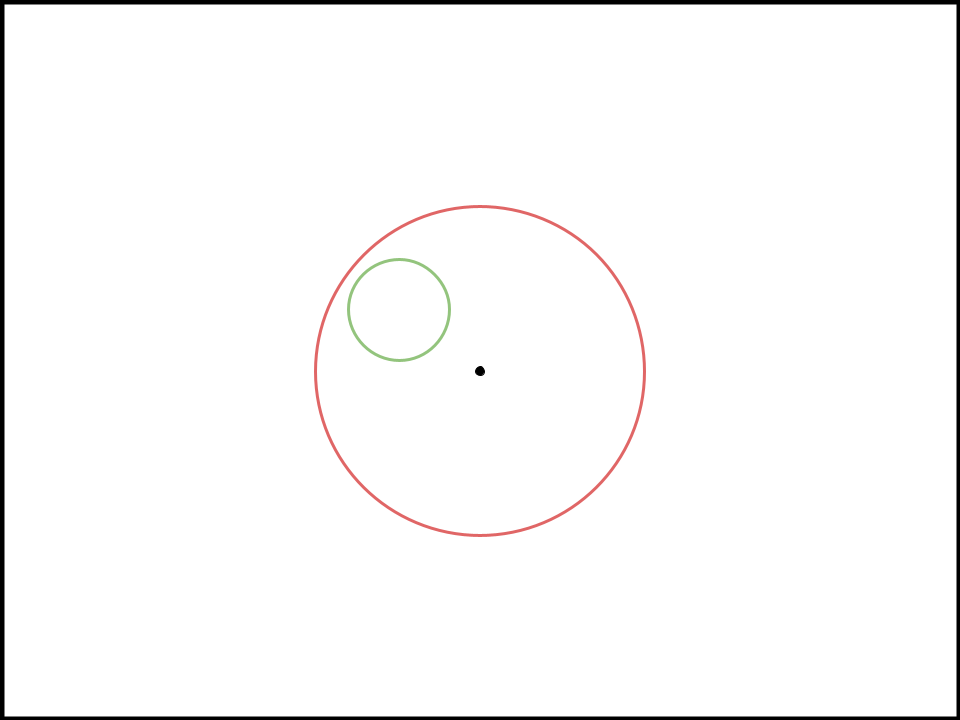

In reality, from a pure predictability standpoint, the circles should probably be about this far apart.

This example should make my point more clear. T: ‘Should’ mandates the plan in the year 2097, March 14, at the 7th hour, 4th minute, and 47th second of the day, presented with no cards, would be very unpredictable. Regardless, the mandates for the two circles should overlap, as an aff that did it along that timeframe would be a topical aff under both interpretations.

But from a pure predictability standpoint, it’s strange to have the circles overlap, since one interpretation is clearly significantly less predictable than the other.

Now, it’s possible we can still represent predictability through this by molding the figure of shapes but it certainly isn’t as simple, clear, or elegant as one would hope for (and the model would seem to indicate that more unlimited interpretations are less predictable).

We do have another model in mind—that exists exclusively to explain predictability.

The Triangle

We’ll start by trying to understand what makes an interpretation of the topic predictable. Predictability matters because of research and is determined through research. It’s precisely why almost every institution starts out by spending multiple hours on a giant T starter packet file. To know what affs are topical or what CPs are competitive, we ought to figure out what the true and correct meanings of the words in the resolution are.

There’s many internal links to predictability that are thrown around in debate rounds. “Intent to define,” “qualifications,” “topic context,” “legal and historical usage,” “plain meaning,” and even normative concerns like limits and ground are all valid internal links to predictability.

The purpose of this article isn’t to break down the internal link debate, as there’s lots of variance and room for disagreement over it, but rather what the impact to predictability is.

Let’s define one unit of research as a certain amount of effort put into figuring out the meaning of the topic (i.e., how predictable each definition is). This effort is universal, and should be the same for everyone. It might be difficult for everyone to reach the same level of effort as certain people have less resources, interpret the topic differently, or don’t speak English etc.

The idea behind predictability is as your units of research increase, the more likely you are to land upon the single most predictable vision of the topic. One unit of research gives you about a 40% chance of correctly figuring out whether or not a ‘basic income’ is universal. The next unit puts you at 75%, the following unit puts you at 85%, and the number keeps slowly climbing higher and higher (but never 100%) as you put in more effort.

Let’s think of the single most predictable interpretation of the topic. When you look at the resolution and look at your best combination of T cards, what does it put together?

It should go something like this:

“The United States federal government” is the three branches based in D.C.

“Should” implies debating over hypothetical action.

“Increase” is to make greater.

“Fiscal redistribution” is taxes OR transfers.

And so on.

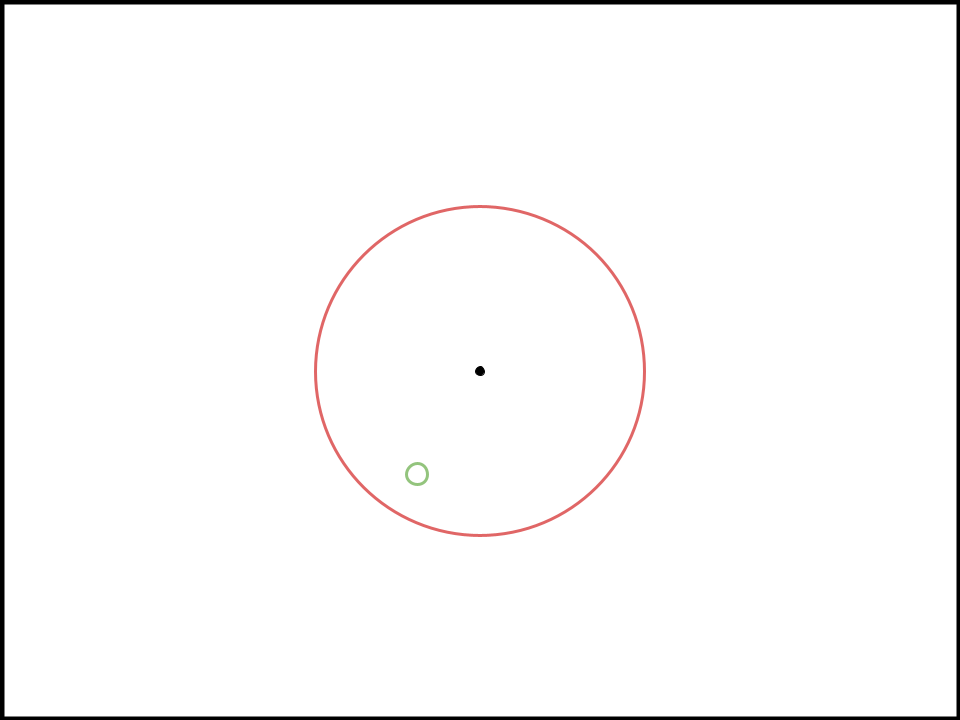

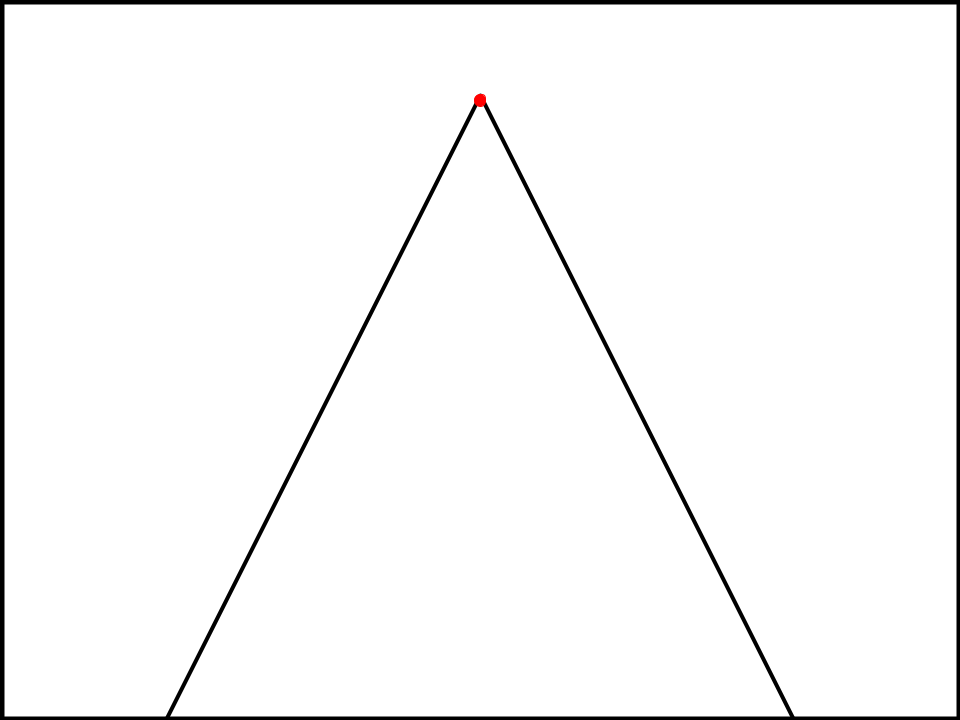

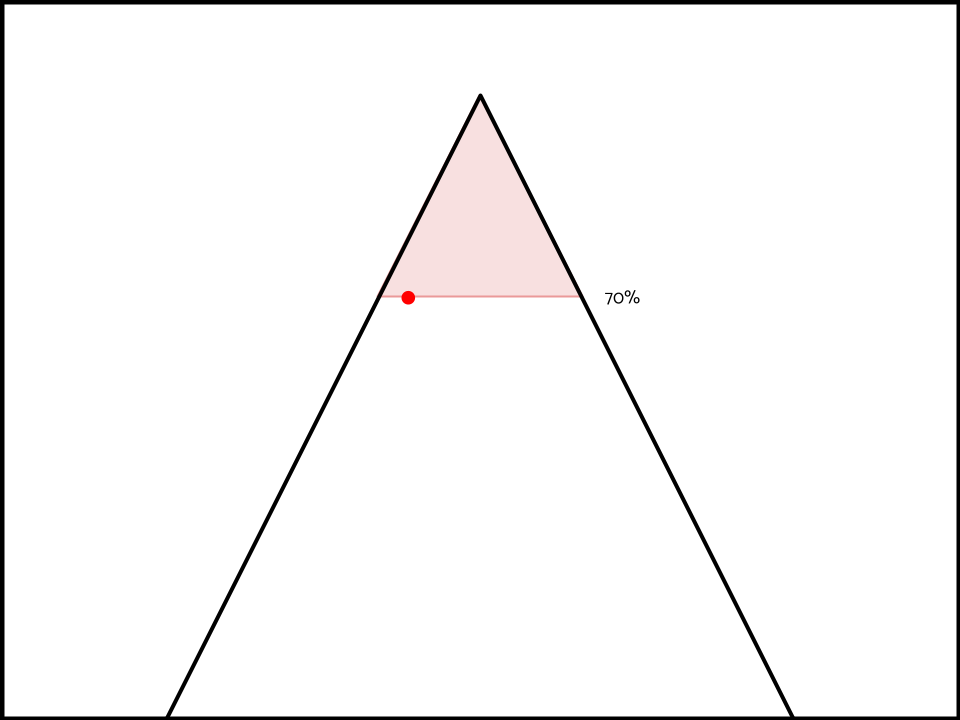

Let's take that interpretation of the topic and put it at the top of a triangle.

The dot at the top of that triangle, is the single most predictable vision of the topic. The culmination of all the units of effort put into figuring out the resolution’s meaning should lead to that dot.

Now, think of some more suboptimal definitions of the resolution.

“Fiscal redistribution” is taxes AND transfers.

“In the United States” includes Guantanamo Bay.

“Substantial” is 10%.

And so on.

Where do these definitions fit into the triangle?

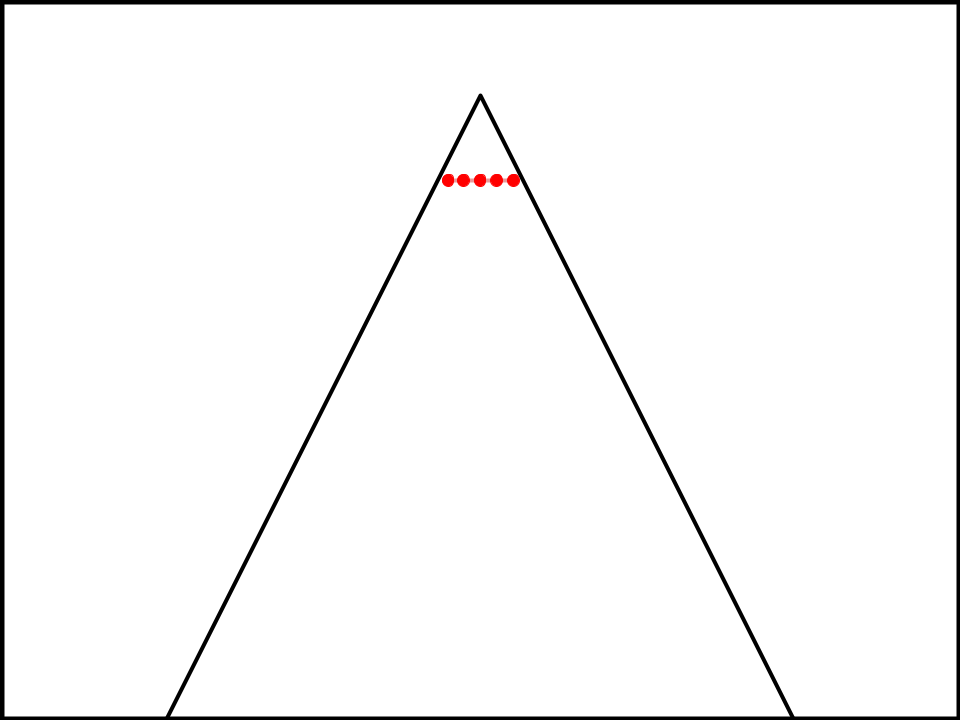

Just under the top, and next to each other. The triangle is theoretically infinitely large where 0% predictability is impossible, but the lower you get, the closer you get to 0%.

Every part of the triangle that isn’t the top is a line with a bunch of dots on it, to represent the different interpretations of the topic that are less and less predictable, with equally predictable interpretations on the same line.

What happens when a team reads one of these definitions? Why is it bad?

The common reasons for this are very apparent and well-known. Research about the substance of the resolution is based around the meaning of its words, so unpredictable interpretations deck research since people would not be prepared to debate an interpretation they could not predict. It’s also unfair to lose a debate when forwarding a factually correct interpretation of the topic.

Forgoing predictability entirely creates a competitive incentive to rush to interpretations of the topic that are best for limits/aff ground but aren’t announced in advance which are unfair and un-researchable for the reasons above, but also crowd out substantive debates that are core of the topic.

Theory would become a cheap-shot that everyone goes for since that becomes the easiest way to win (since teams couldn’t prepare answers to every possible violation) and there’s infinite things both sides can do better which makes ground concessionary and allows the side forwarding the unpredictable interpretation to monopolize preparation.

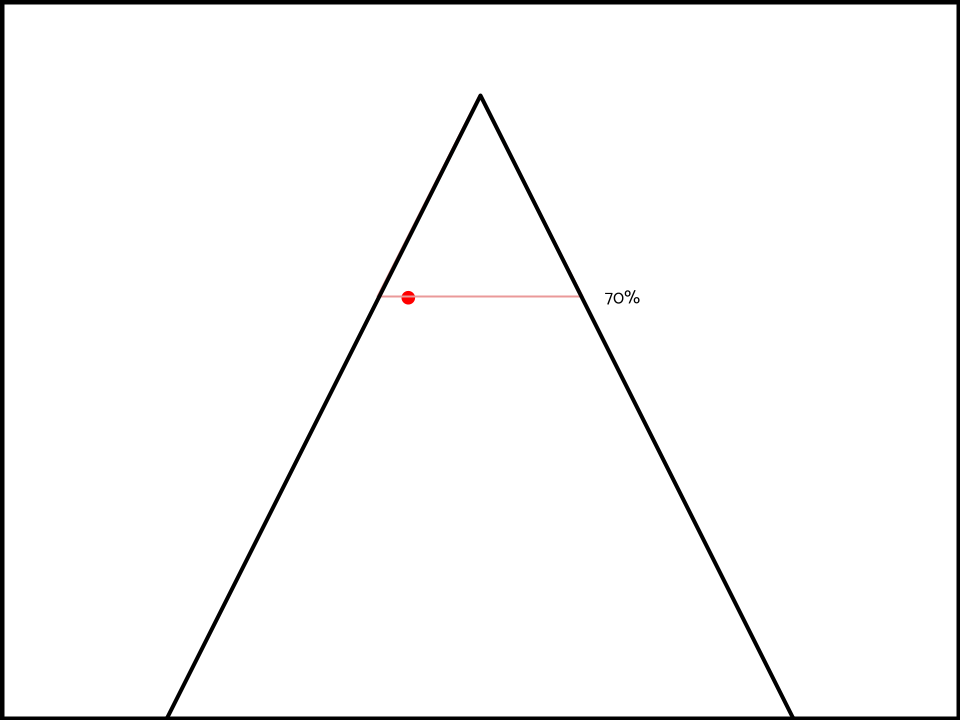

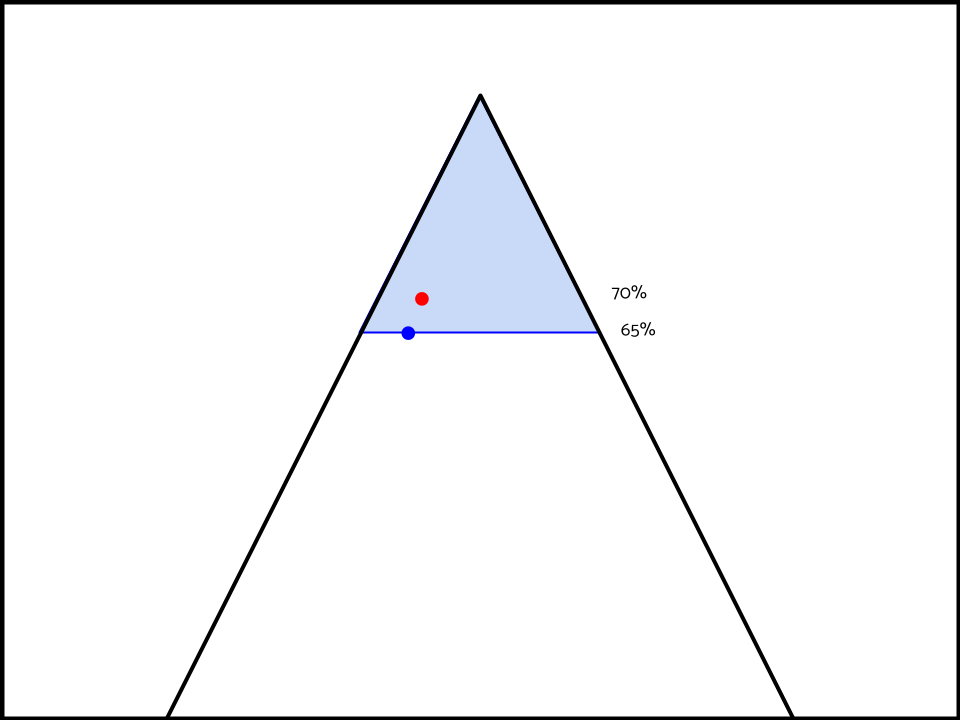

But what about the spill-over effect? If your opponent expects you to be prepared for an interpretation that’s 70% predictable.

Then they also logically expect you to be prepared for other interpretations of the topic that are equally as predictable (70%).

AND interpretations of the topic that are more predictable than 70% as per the unit of research thesis above.

A flavor of this argument is made in K debates a lot. When the aff team states: ‘Counter-interpretation: Just our aff!’ The most common neg answer is that the affirmative model doesn’t just justify just its own model, but instead every equally predictable or more predictable interpretation, so the limits and ground DAs still apply.

What I don’t understand is why this is not a more common argument in policy debates. If what’s said above is true, then the spill-over effect of the less predictable interpretation always includes the other side’s interpretation too, making the debatability impact link back harder.

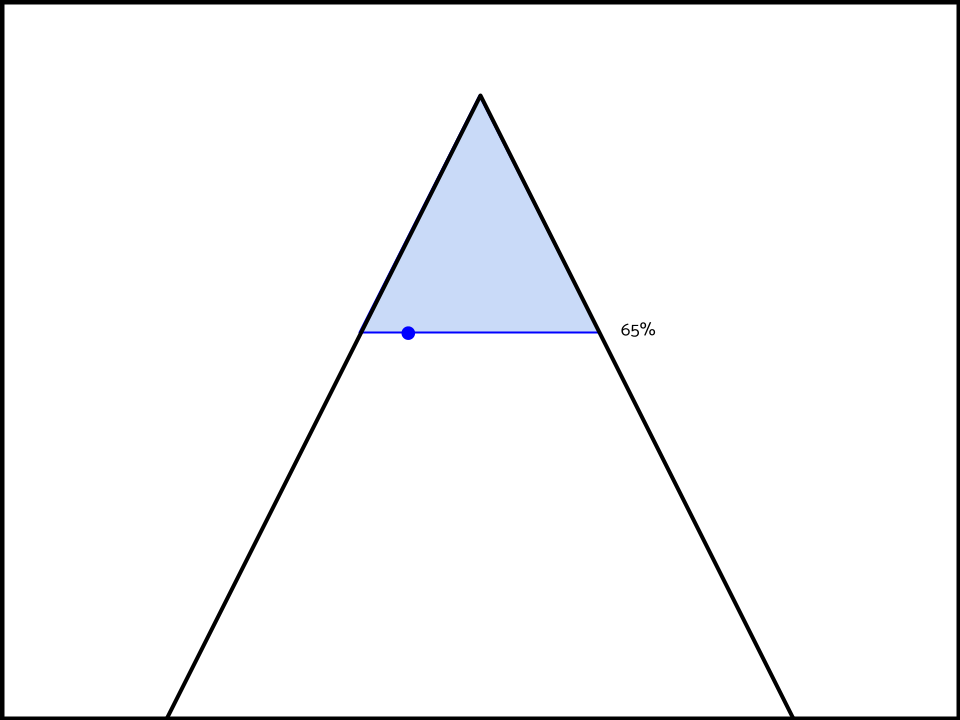

Take for instance, the aff has won that their interpretation is 70% predictable, and that their opponent’s is 65% predictable. But has lost that their interpretation deletes neg ground, has a huge limits case and no aff ground/aff flex case.

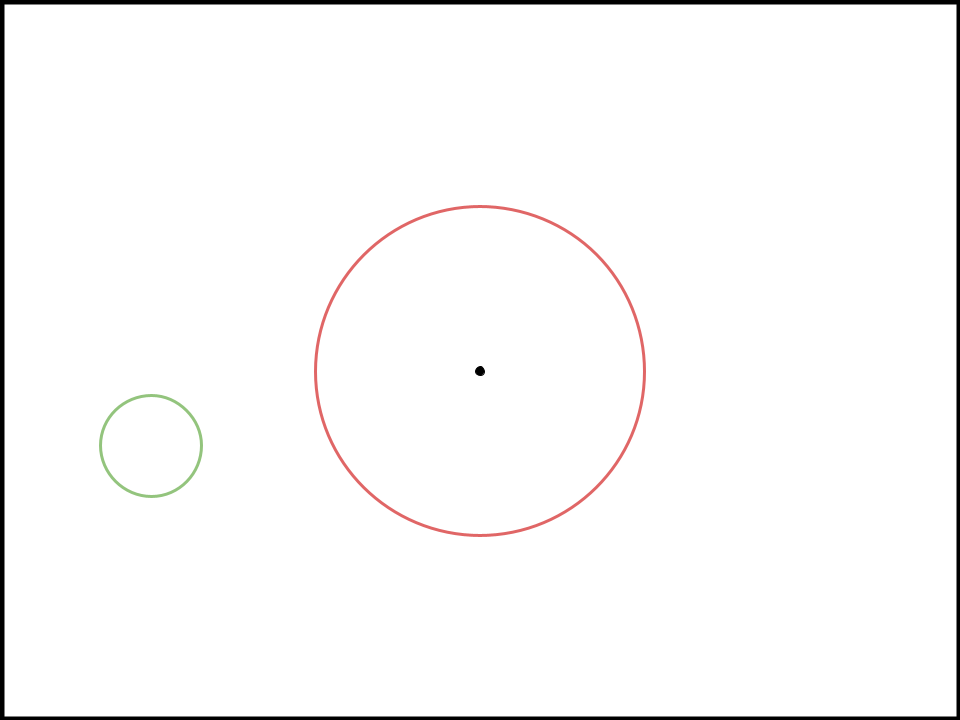

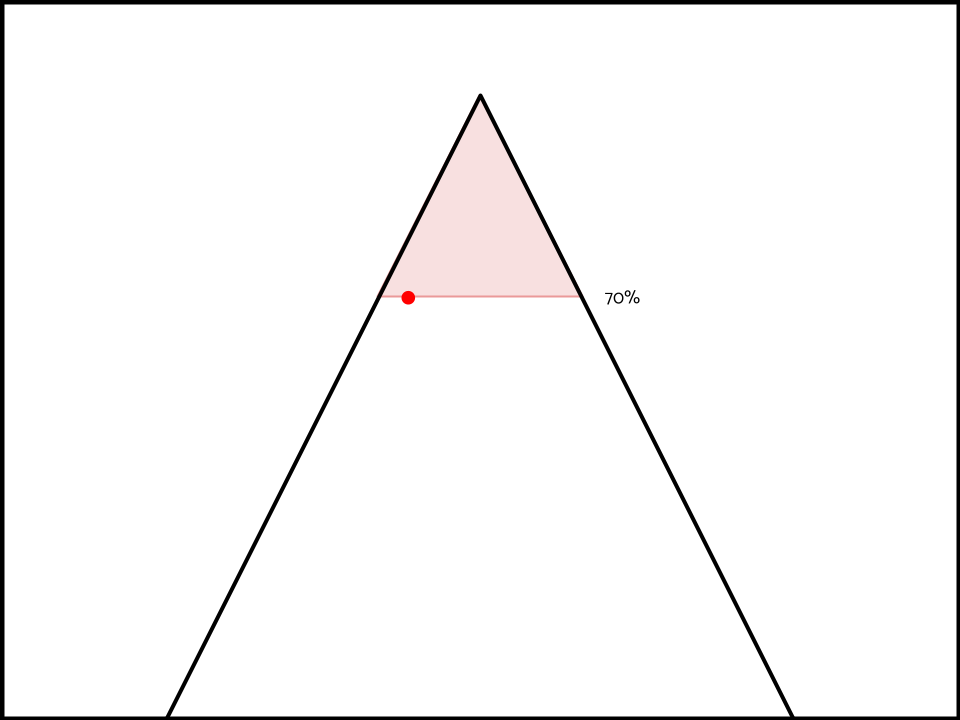

The sole spill-over impact to predictability in this scenario results in the aff’s model justifying these interpretations.

And the neg’s model justifying these.

The spill-over effect generated from the neg’s interpretation includes the aff’s interpretation and a bunch of other random visions of the topic.

This would imply that every debatability impact the neg forwards, links back to themself harder.

All Models Are Flawed

As said at the top of this article, all models are flawed, some models are useful.

This equally applies to the predictability triangle.

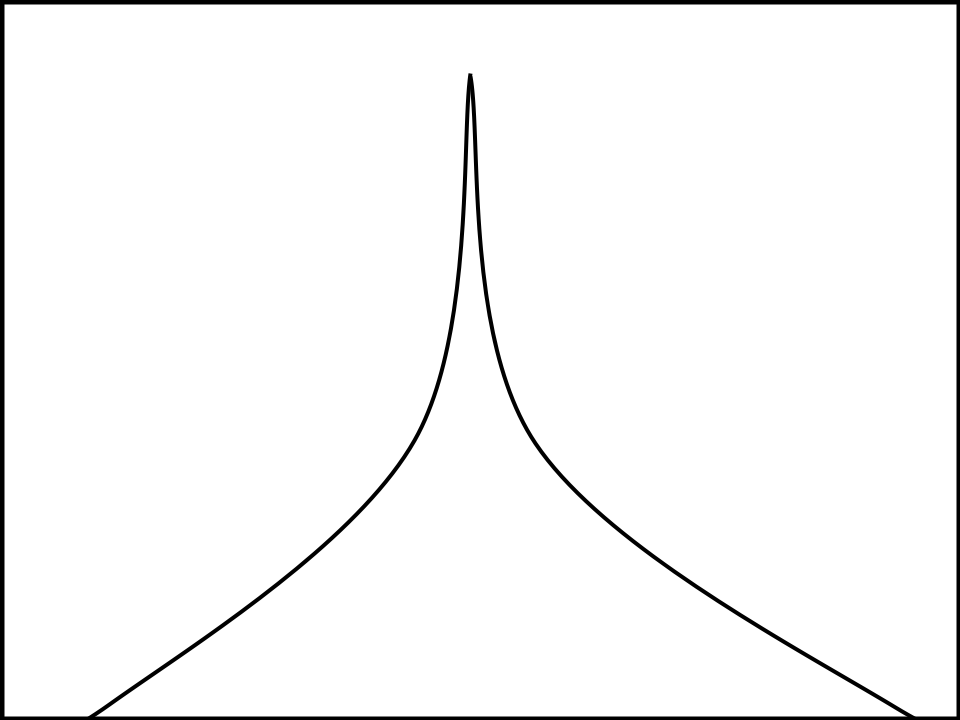

One can say that as you get more unpredictable, there’s an increase in the quantity of unpredictable interpretations which causes the edges of the triangle to be curved, something like this.

And one can say that it’s mathematically impossible for two interpretations to be equally predictable, so the triangle is actually just a straight line that’s infinitely long.

This view actually makes it more apparent to why it has to be ‘CI: Only our aff’ justifies not only every equally predictable interpretation, but also every interpretation that’s more predictable.

These criticisms are all valid and good. The point of the predictability triangle is not to have a model that can explain every interaction that predictability encounters, but rather to have a simplistic model to explain some more complex debate mechanics.

Conclusion

Nothing stated in this article is fact and there is a lot of room for disagreement. The point of it is to start discussions in debate enclaves and offer a different way to teach debate to newer people in the activity.

There’s many ways to refute this article and I’m interested in seeing what people come up with. If you have any questions, disagreements, comments, or concerns, feel free to email both me and Pranav and we’ll try to get back to you as soon as possible.