The Resolutional Circle

An explanation of debate mechanics using a single diagram.

Introduction

Imagine this blank area represents anything that you could say in a debate round, including a topical 1AC about basic income, a critical affirmative about Asian semiotics, and even random non-English sounds or ululations.

This is the scope of the potential possibilities of an affirmative.

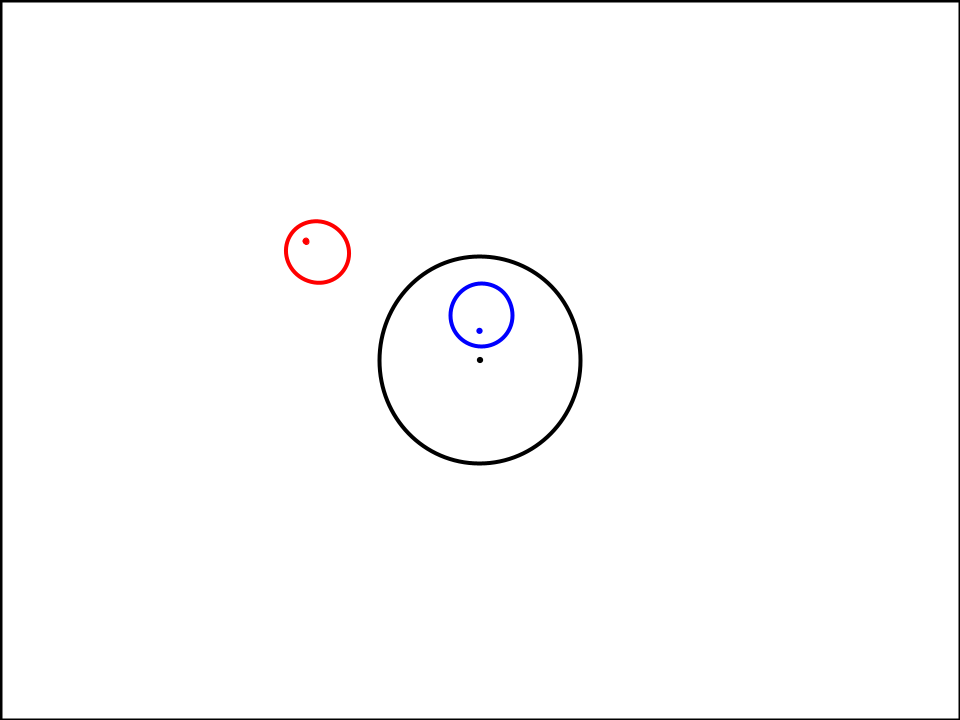

Now, imagine this circle includes all things that we could say in a 1AC that are topical. In reality, this circle would be very small (because topical affs may not even be 0.0000001% of the things we could say in a round), but has been inflated for the purposes of this article.

Topicality arguments determine the size and position of the resolutional circle.

The size of the circle represents limits, whilst the contents/quality of argumentation within the circle represent ground. Everything within the resolutional circle is aff ground, and everything outside of it is neg ground.

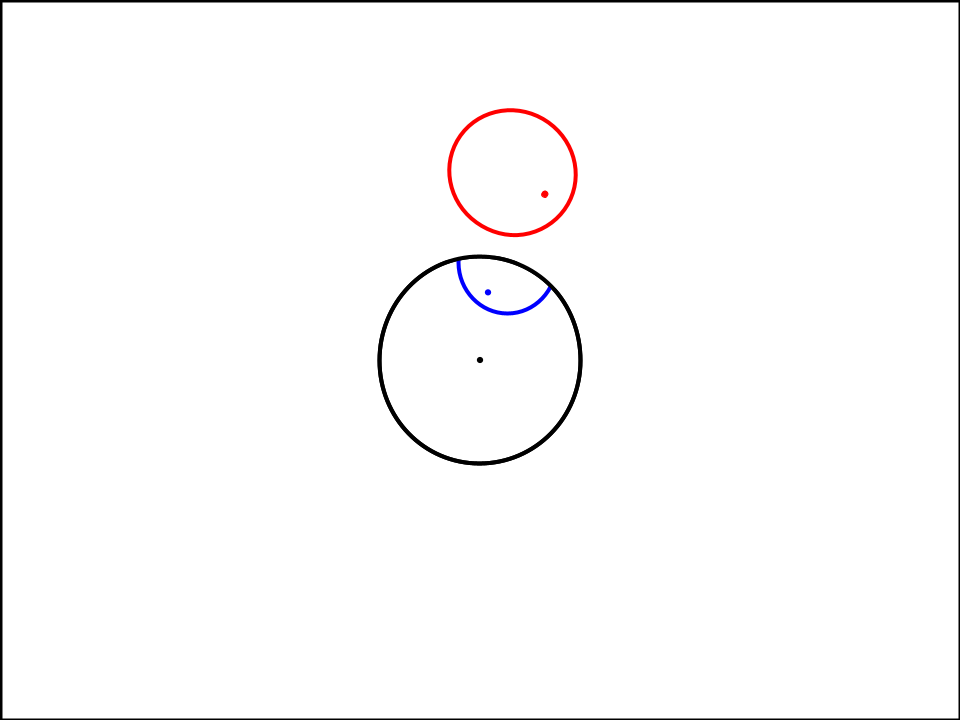

Here, I have depicted two circles: one represents the topicality argument that ‘should’ is “immediate” (red), whilst the other represents the argument that it is “not immediate” (blue).

The most predictable reading of the resolution would be centered at the center of the area, and the farther that the ‘center’ of an interpretation gets from the ‘center’ of the area, the less predictable it is*.

In the drawing above, “T: Should is not immediate” is depicted as “100% predictable” and comparatively less limited than “T: Should is immediate,” which is depicted as less predictable.

* We understand that ‘distance from the center’ isn’t the best way to represent predictability, but it’s just used here for simplicity. There will likely be future articles explaining this concept using different models.

Now, how would we determine which of these interpretations is more desirable? They’re both equally predictable, and equally limited. The answer is ground, the quality of argumentation within each circle*.

The colored circles in the above diagrams show the affirmative’s mandate which determines whether or not it violates topicality or makes a counterplan competitive.

* This model is bad at representing ground. An ideal model would be three-dimensional, with the roughness or topography of the area representing quality of ground.

Affirmatives

Now that we’ve explained how the model represents the standard impacts to topicality (limits, predictability, ground), we can examine how it interacts with individual affirmatives.

We will discuss affirmatives through some competition models. There are many (maybe even infinite) models—planicality, positionality, and resolutionality are the most common ones debated.

Planicality

Planicality (Plan + topicality), more commonly known as plan text in a vacuum, argues that the affirmative’s mandate is determined solely by the words in the plan text.

Let’s go back to our original, most predictable interpret`ation of the resolution:

The ‘center dot’ of the circle is likely normal means of the text of the resolution itself, whilst every dot within the circle is a possible means of the resolution.

Inside this circle lies “The United States federal government should expand Social Security within United States territories,” represented by the red circle and dot here:

The dot represents normal means of this plan text. It is the most likely way that it is implemented (the courts overturn United States v. Vaello-Madero, directing Congress to expand Social Security to territories, who pass a bill directing the Social Security administration to do so, causing the Social Security administration to administer benefits to territories, etc).

The red circle represents all possible ways this plan text could be implemented. Some may involve expansion of a tax, some may provide Social Security to a limited group of territories, and some might a decrease in fiscal redistribution.

Plan in a vacuum says that the plan text is the sole determiner of the mandates of the plan—aff specification in cross, evidence, etc. is irrelevant.

Why are some possible implementations of this plan text outside of the resolutional circle? It is because some possible implementations of the plan text are not topical (i.e. the ‘a decrease in fiscal redistribution’ example from above).

To explain further, zooming out, imagine this scenario:

The red circle represents the plan text: “The United States should do something.”

This affirmative meets topicality in a vacuum, because some possible implementations of it are topical. This is because topicality is a negative burden, where the negative has to prove that the affirmative (in this case, the plan) in no instance meets topicality.

This argument is most commonly deployed against topicality violations premised off positions that the affirmative takes—as a counter-model. It also applies to counterplans that don’t compete off the plan.

Positionality

Positionality (Position + topicality), or positional competition, argues that the mandates of an affirmative are determined by the position it takes—including tags, cross, highlighting, solvency evidence, etc.

Imagine the same plan text from planicality:

“The United States federal government should expand Social Security within United States territories.”

The affirmative, in cross, says that this plan text actually mandates a no-nuclear-first-use agreement. Planicality would argue that the diagram does not change, but positionality argues that the diagram would be this:

This diagram shows that the words in the plan text are irrelevant—since the mandates of the affirmative are determined only by how the affirmative team characterizes the action of the plan.

This argument is most commonly deployed by the negative team in order to garner competition for counterplans or violations for topicality in an instance where violations/competition off the affirmative’s plan text are not sufficient.

Resolutionality

Resolutionality (Resolution + topicality), commonly referred to as resolutional competition, means that the plan’s mandate is determined by the words in the plan text given resolutional context.

Taking the same territories example—resolutionality means that possible implementations of the plan that are not topical are no longer aff ground, making the diagram look like this:

This is similar to planicality, the only difference being that all extra-topical or non-topical possible means of a plan text are not aff ground.

This argument is most commonly deployed against affirmatives whose plan texts exclude resolutional language, allowing the neg to garner competition off the resolution itself. For example, the offsets CP* can compete off the words “increase by” in the resolution, which most affirmative teams have opted to exclude from their plan texts.

Under a model of resolutionality, affirmatives can only fiat mandates that are within the resolutional circle. If the plan’s entire circle is outside of the resolution, then the whole action of the aff is deemed exclusive from aff ground. A precise interpretation of this phenomenon might involve affs that are entirely exclusive with the resolution losing to presumption, not topicality—but either way, entirely exclusive affs still lose.

* The offsets CP is a counterplan that PICs out of the the word ‘increase,’ fiating a ‘net decrease’ in fiscal redistribution (for this year’s topic). It still does every other mandate of the plan, but “offsets” the plan’s increase with a compensating decrease in fiscal redistribution.

Counterplans

The biggest question for counterplans is the affirmative’s mandate. This mandate, as discussed above, can be determined in a multitude of ways. Regardless, no matter the competition model, competition is purely based off the mandate of the affirmative.

Consider this example:

The blue circle is a affirmative (lets say, for example, “The United States federal government should substantially increase fiscal redistribution in the United States by adopting a federal jobs guarantee”), and the red circle is a counterplan (“The United States federal government should adopt a nuclear no-first-use agreement.”)

No possible implementation of the plan can be the counterplan, and vice versa, indicating that the counterplan beats “perm: do the CP,” because it is not a possible means for the plan.

Now, consider this situation:

This counterplan loses to “perm: do the CP,” because the the mandate of the CP is a possible means for the mandate of the plan text. The normal means of the CP is irrelevant, because competition is solely a question of mandates.

For example, “Plan: The United States federal government should provide means-tested welfare,” and “CP: The United States federal government should enact progressive economic policy.” Let’s assume that normal means of the CP is to provide a universal basic income (something that in no instance can be means-tested welfare). The CP still does not compete, because the mandate of the CP is a possible implementation of the plan.

The reason the prior section did not discuss normal means as a competition model is because it is nonsense. This has been a motif throughout this article, but competition is based purely off mandates. Normal means is simply the most likely effect of the plan. It is not distinct from a claim of the effects of the plan solving an impact, such as nuclear war.

For example, take the UBI aff. What is the most likely way that the federal government would provide it? First, we would probably see a section of the democratic caucus persuading other liberal members in Congress to vote for the proposal. There would likely be partisan infighting. Biden would probably have to get involved in order to get sufficient votes from both sides of the political aisle. This is your common political capital or bipartisanship link story for the politics DA.

Or, republicans could horse-trade the bill for enormous tax cuts, resulting in the cumulative policy ending up being immensely popular on both sides without Biden’s involvement.

Both of these scenarios could be a result of the mandate “The United States federal government should provide a basic income.”

A mandate of the aff is an action that must always occur in a world of the plan’s enactment—whereas the normal means or other possible means of the plan are simply likely, but uncertain effects.

Now, how do planicality and resolutionality interact regarding competition? Consider this example:

Resolution: The United States federal government should substantially increase fiscal redistribution in the United States by adopting a federal jobs guarantee, expanding Social Security, and/or providing a basic income.

Plan: The United States federal government should substantially fiscally redistribute in the United States by providing a basic income.

Counterplan: The United States federal government should decrease fiscal redistribution in the United States by providing a basic income and exempting innovative activities from taxation.

In a model of planicality, the diagram looks like this:

The counterplan does not compete, because the affirmative does not include the mandate to increase fiscal redistribution.

In a model of resolutionality, the diagram looks like this:

The counterplan does compete, because non-topical implementations of the plan text are no longer possible implementations of the affirmative. All affirmatives must mandate an increase in fiscal redistribution, and thus, the negative gets the PIC out of that mandate.

We’d love to hear your thoughts below—and you can email us at roy100406@gmail.com [Ishan] and nanomantis07@gmail.com [Pranav].

Ishan's debate opps cut 10 cards today and he's writing about the 4 dimensional topicality hexagon

wouldn't a model of positionality mean that competition can be garnered off normal means?

eg. if the negative clarifies normal means in cross by asking what federal agencies would be involved in implementing the aff, they could theoretically PIC out of those agencies?

Or, if the aff claims an advantage off normal means of the plan eg. a soft left aff claims that building indigenous adaptation would mean giving the land back---the neg could PIC out of that since it was part of the position the aff takes?